Very much drawn to pastels, I’m still hesitating to use them as I find the instability of the powder slightly disconcerting (like water in water colours)

Painting is a practice of the physical kind, empirical, and the more we ask ourselves questions before using it, the more we put off confronting the material, this union of artist and medium that is indispensable in creating a work of art.

But the physical and mental aspects involved have an equal influence over each other and perhaps for the moment you are going through an expectative period where an artist instinctively feels an impulse towards the right material but doesn’t dare to put it to the test as you feel you are not quite ready; a bit like postponing an encounter with something that we hold sacred! In the meantime, all kinds of materials can act as a basis for an apprenticeship in the quest for truth and it might just be that one day that will be pastels.

The instability of the powder, the instability of water, opens up the way for an adventure in artistic exploration… a land of discovery, a world just ready for the taking …

Feeling like you can’t master the effects.

Just as the artist dominates the material so the material dominates the artist, and artistic production comes about through this perpetual jousting. It is true that with pastels, the artist has the impression of accommodating and adapting the material rather than mastering it!

But isn’t it just this state of acceptation and availability that allows the artist to progress in the technique, to penetrate its secrets and sometimes to the point of finding inspiration in it? By wanting too much control we run the risk of not being able to reinvent ourselves!

Soft pastel is made up of pigments almost in their pure state as they have only been very slightly modified by nature or by the binding agent or other additive, which is very rare occurrence in pictorial art! This specificity is what makes pastel powder so unusual: a heavy touch of matter nevertheless adheres to the pores of the support by nothing more than a thread! The powder is light, volatile, but in fine layers it sticks relatively well to the support and the mark it leaves, once blended, has the persistent tenacity of pigments!

The instability of pastel powder gives the artist the impression of losing a grasp on reality, slipping into a vaporous and misty area. Especially as the capricious powder has the atmospheric power of moving from abruptly and irremediably buried lighting effects to magical ones springing out of a certain body language purely by chance!

We learn then to work and create with the material, and in new ways, given the wide diversity of textures that the rich pigments of pastels induce In this way, the powder’s instability prepares the artist for adventure.

Pastel, primary material, carries a diversity of resources in gestation:

Sticks offer the direct intensity of their pure colour. Depending on the pressure applied to the stick, the colour can either have the lightness of a breath enabling the grain of the paper to show through, or can be more or less concealing and opaque.

Two superimposed colours do not always result in exactly the desired nuances, but on the contrary often surprise us by creating tonalities with an unexpected brightness. Colours that have been spread out can be blended by shading.

The edge of the stick can be used for all kinds of graphics. When superimposed, the lines leave the way open for optical effects of both matter and depth.

And pastel hasn’t yet revealed how it lends itself perfectly to mixed techniques! Through highlighting, the pastel lines generously nourish the work with their rich texture. When in contact with mediums that have a good level of adherence to the support, pastel consolidates itself rather like an incandescent parasite!

Moreover, pastel is a medium whose facture is just as expressive in drawing as it is in painting! Some lines on a sheet of paper and the opulence of substance, intensity of colour, vibrations of light spring forth. Powerful are the lines of a spartan pastel drawing! Just like paint in painting, when the powder completely covers the support, the excess of rich matter risks at worst, annihilating itself.

Here are some innovative examples from works by painters with an intimist sensibility: Chardin, Degas, Redon, Rouault.

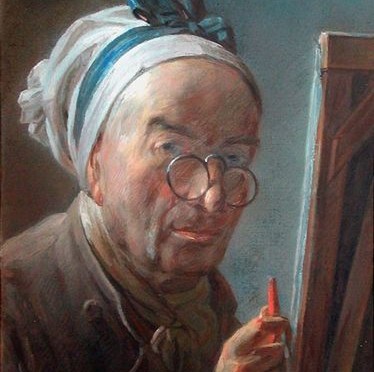

Jean Siméon Chardin

“We use colours but we paint with emotion!” ChardinChardin, who came to pastels late in life, had the authority to take it by storm with complete impudence, countering the seductive and refined texture of the academic style of pastel painting seen during the eighteenth century, wanting to show instead the hierarchical equality of pastels with oil painting. (Rosalba Carriera, Quentin de la Tour, Perroneau, Liotard …)Chardin’s “emotion” must have been very powerful given the force of his highly individualised touches of pastel, left in their raw state, thick, square, and juxtaposed with unblended surfaces, unique to the palpitation of a pigmented grain.

Chardin’s technical innovations were almost certainly linked in part to his ever-diminishing sight, which he compensated for, by using some audacious effects of colour and material. For the same reasons, Degas also unleashed himself through pastels.

This meditative self-portrait, very much in half-light, is one of his last works. The gaze, already detached from the world, nevertheless meets the spectator’s gaze with determination in a benevolent sign of transmission. Crushed fragments of vermillion red on the artist’s hands and on parts of his face, contrasted with green and blue glimmers, are pre-cursors of Fauvism and the colorists of modern painting from Jawlenski to de Staël.

And highlighted in the portrait, coming out of the artist’s hand, the ardent red of this pastel stick, charged with a fervent silence like a hand lit by a candle in a work by Georges de La Tour! Pierre Rosenberg (art historian) commented on the symbolism of this stick “In his last pastel, Chardin uses a single red spot to represent a colour crayon. A way of saying: right up until the end, that’s how I’m going to express myself.”

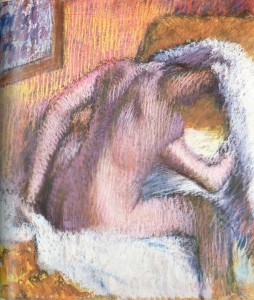

Edgar Degas

The substance of Degas’ pastels is created through lines, drawing being primordial in his work. Degas is able to multiply the superposition of pastel powder because he fixes every layer. Networks of lively hatching, tangled up by way of the superpositions, create depth, transparencies, pearly reflections, a full luxurious thickness just like the flesh tamed with bright highlights of his later nudes.

The nude observed here appears to go beyond the dissonant boundaries of the colours customarily used by the painter. Degas, with his fading vision, frees himself from notions of perfecting this model whom he had already painted in numerous series to the point of saturation! Notice to what extent the frantic strokes of milky pastel shine on the hatched grain of the dark half-tints of the primers.

The nude thus finds all of it resonant autonomy and the two pieces of the white towel open up like a seashell on the rosy pink thigh of a nymph, clashing on the salmon background, with its pink and yellow hatching, of the wallpaper!

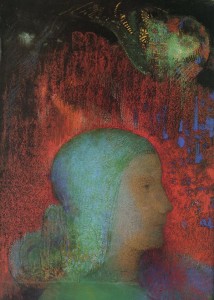

Odilon Redon

The unsure contours of works done in pastels suit Redon, an inward-looking painter. Fleeting, evocative effects, diffused modelling, ephemeral texture. “My drawings inspire and do not define themselves. They do not determine anything. They put us, just like music, in the ambiguous world of the indeterminate”

In Redon’s work the pastel gently brushes the support. This is the case in this symbolic portrait of Joan of Arc. One layer of freehand pastel is enough to make the colour vibrate.

The Cadmium red powder laid on the black paper support, contrasted in the interstices with some touches of ultramarine and brightened by a bit of yellow in places, ripples with light; the red becomes a forest of magma from which is cut out the impassive profile of the subject topped with a chignon abundant with phosphorescent tracery chiselled out like leaves on a stained glass window, (is there a divinity meditating there?) finally veiled by the blending and a dusting of sulphate!

Moreover, the simplicity of the composition is exactly what gives the work its intemporality. A profile emerging from a fresco by Piero della Francesca or a modern day comic book? The bubble, blown like glass, in pastel that hasn’t fused together, directly onto the black background, gleams like a crystal ball; descending from the depths of the sky like a cosmic fish!

Georges Rouault

Pastel really works well when used with other techniques. It brings out the best in other them, whether it be heightening or a mix of methods. In addition, when mixed with other mediums, notably aqueous ones, the pigments have an even better adherence to the support.

“A Tabarin” is a spirited work, created in a farandole of powder and water. On the crest of the wave, the ferocity of the dancer surges forth in a whirling latticework of watercolour and a scattering of Blue Persian and mauvish-red pastel.

The pastel balances out this flight of lyricism sometimes with little puddles of watercolour, sometimes covering up areas of watercolour in certain places, with nervous highlighting. The two mediums soak each other up to the point where they melt into one, except where the pastel is spread out very thinly on the white areas of the paper.